A Trial That Captivated a Nation

In July 1925, the once sleepy town of Dayton, Tennessee became the stage for one of America’s most famous trials. High school teacher John T. Scopes was charged with violating the state’s 1925 Butler Act, which prohibited teaching “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”1 The trial became known as the “Scopes Monkey Trial” because it centered on the teaching of human evolution, which opponents and many in the press sensationalized as the assertion that humans had descended from monkeys.

The Scopes Trial quickly became a media circus. The Nation declared that the “Battle of Tennessee may play as significant a part in American history as the Battle of Gettysburg” while the Christian Register wondered whether it would become “a spectacle staged by buffoons for a summer holiday.” The Crisis, a publication of the NAACP, supplied a more sober description:

…the learned American press is emitting huge guffaws and peals of Brobdingnagian laughter combined with streaming tears. But few are deceived, even those who joke and slap each other on the back. The truth is and we know it: Dayton, Tennessee, is America: a great, ignorant, simpleminded land… (see first paragraph).

For the first time in US history, a trial was broadcast on the radio. Reporters from across the country and around the world travelled to Dayton. Over a hundred newspapers were represented in the crowded courtroom2.

Trial Overview

Trial Overview

The Time magazine “capsule” for 1925 called the trial “one of the most colorful chapters in American history,” and mocked both sides in its overview. While both the prosecution and defense wanted what Williams Jennings Bryan called a “duel to the death” and hoped the case would reach the United States Supreme Court, the courts of Tennessee apparently viewed all the fuss as much ado about nothing and agreed with the position postulated by prominent cultural critic H. L. Mencken in The Nation magazine:

“No principle is at stake at Dayton save the principle that school teachers, like plumbers, should stick to the job that is set before them, and not go roving about the house, breaking windows, raiding the cellar, and demoralizing the children. The issue of free speech is quite irrelevant. When a pedagogue takes his oath of office, he renounces his right to free speech quite as certainly as a bishop does, or a colonel in the army, or an editorial writer on a newspaper.” (right column third paragraph)

For additional overviews of the trial, see the primary sources section below.

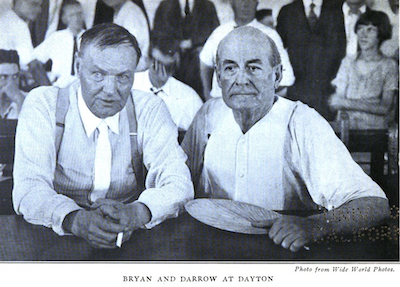

The Three Protagonists

In Dayton, two of the country’s best-known public figures faced off. Leading the prosecution was populist champion Williams Jennings Bryan, the three-time presidential candidate and former secretary of state known as the "Great Commoner”. For the defense, Clarence Darrow, was the fiery criminal defense attorney and agnostic who had become nationally famous for his 2024 defense of Leopold and Loeb3. The defendant John T. Scopes was only 24, and had just finished his first year of teaching when he became the center of a media storm and national debate surrounding the trial.

William Jennings Bryan, though derided by journalists, was a complex figure. A progressive reformer, he championed women’s suffrage, a federal income tax, publicizing campaign contributions, and peace. Yet, he was also a religious conservative and at the time of the Scope’s Trial, he was the most famous fundamentalist Christian spokesperson in the country4. He believed that studying evolution caused people to lose their religious faith. During Darrow’s famous cross-examination of Bryan at trial, and in Bryan's prepared address to the jury, he cited Darwin’s own writings (and the writings of other 19th Century evolutionists) as evidence to prove that evolution caused them to disavow their faith and become agnostic.

Bryan was a prolific writer and much of his work is in HathiTrust, including early issues of The Commoner, a newspaper he owned and published; his Memoir; and his address to the jury which, intended for the jury at the Scopes Trial, was published just days after the trial ended and only a few hours before his unexpected death.

Clarence Darrow was a civil libertarian who believed that criminalizing classroom speech and the teaching of evolution was the first step on a slippery slope that could lead to the return of medieval ignorance and religious violence. On the trial’s first day, in an effort to have the Butler Act declared unconstitutional, Darrow delivered a long impassioned speech arguing that the act violated freedom of religion, stating "we find today as brazen and as bold an attempt to destroy learning as was ever made in the Middle Ages, and the only difference is we have not provided that they shall be burned at the stake…”

Darrow was also a prolific writer and many of his works (both fiction and non-fiction) are in HathiTrust. His writings tend to focus on matters of criminology rather than evolution or the Scope’s trial, but, his 1932 biography (currently search-only because it is still in copyright5 until 2028), is an exception and includes his thoughts about the trial. Notable works in Hathitrust include his 1904 autobiographical novel, Farmington, and his 1922 Crime: Its Cause and Treatment.

The defendant John T. Scopes was found guilty and fined $100. Following the trial, Scopes left teaching to attend graduate school in geology, and he avoided the media spotlight. He said little during the trial but spoke powerfully at its conclusion:

“I feel that I have been convicted of having violated an unjust statute. I will continue...to oppose this law in any way I can.”

It wasn’t until 1967, when he published his memoir,6 that Scopes’ voice was added to the many narratives about the trial.

While the trial and press accounts seemingly pitted Bryan’s fundamentalism against Darrow’s agnosticism, the core of the debate over evolution at the time reflected the broader cultural conflict in American protestantism between traditionalists (or fundamentalists) who saw evolution as an attack on biblical truth, and religious modernists who believed science and religion could coexist7. A handful of resources demonstrating the conflict are highlighted in the primary sources section below.

Outcome and Aftermath

The trial ended after only eight days: when the judge barred expert scientific testimony and struck Darrow's cross examination of Bryan, the defense requested a guilty verdict so that they could appeal to the Tennessee Supreme Court. It took the jury only nine minutes to deliberate and convict Scopes8. The case was appealed, and two years later the Tennessee Supreme Court upheld the Butler Act but overturned Scopes’ fine - thus preventing further appeal9.

The result of the trial meant that public school and university teachers in Tennessee were prohibited from teaching evolution until 1967, when the Butler Act was finally repealed by the state legislature10.

In the years immediately following the Scopes trial, two states enacted similar anti-evolution legislation: Mississippi in 1926, and Arkansas in 192811. While other states may not have enacted laws, strong opposition to evolution had a chilling effect on school districts, teachers, and textbook publishers beyond Tennessee and the South12. It wasn’t until 1968, when the US was engaged in a space race with the Soviet Union and science education was of national interest, that an unanimous United States Supreme Court overturned Arkansas’ statute and ruled that to outlaw the teaching of evolutionary theory in the classroom was a violation of the establishment clause of the First Amendment13. While the Supreme Court’s decision seemingly established national law on the issue once and for all, both legal and cultural challenges to teaching evolution have continued to surface14.

Why It Still Resonates

A century later, the conflicts raised in the Scopes Monkey Trial remain all too relevant, particularly given the current attacks on scientific research, public health, and climate science. The Scopes trial revealed core tensions in American democracy, including public education vs. religious doctrine, the rights of minorities vs. majorities, parental vs. state control over how children are educated, free speech, and academic freedom.

HathiTrust Primary Sources

Trial Overviews

- The trial transcript in The World's Most Famous Court Trial: Tennessee Evolution Case (1925).

- The War on Modern Science; A Short History of the Fundamentalist Attacks on Evolution and Modernism (1927) by Maynard Shipley - see the chapter on the trial.

- Bryan and Darrow at Dayton: the Record and Documents of the "Bible-evolution Trial" edited and compiled by Leslie H. Allen (1925).

- Bryan, the Great Commoner (1928) by John Cuthbert Long - see the trial description.

Religious Modernists vs. Traditionalists

- Charles Francis Potter, a Unitarian minister and modernist, attended the trial as Darrow’s biblical advisor. In his autobiography, he recalls staying in Dayton’s “Monkey House,” where the defense team lived together and plotted their strategy. They were joined one night by an unusual dinner guest - Joe Mendes, a trained chimpanzee.

- Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History, countered anti-evolution rhetoric in his works:

- The Earth Speaks to Bryan (1925)

- Evolution and Religion in Education, Polemics of the Fundamentalist Controversy of 1922 to 1926 (1926)

- From the Greeks to Darwin: the Development of the Evolution Idea Through Twenty-four Centuries documents the history of evolution before Darwin. Osborn republished his 1894 book in 1926.

- Edwin Brewster, a science writer, published Creation; a History of Non-evolutionary Theories (1927) provides a general history of creationist ideas.

- In a 1925 editorial, The American Hebrew magazine shows that the conflict between modernists and traditionalists expanded beyond protestantism.

The Textbooks

Two textbooks were discussed at the trial.

- The textbook Scopes used to teach evolution, A Civic Biology: Presented in Problems and the textbook which replaced it,

- Biology and Human Welfare which did not include information about evolution. In 1926, a new edition of A Civic Biology was published with the chapter on evolution removed15.

Footnotes

1Tennessee Virtual Archive, The Butler Act 44122_001. (n.d.). https://teva.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/scopes/id/168/

2ACLU, State of Tennessee v. Scopes https://www.aclu.org/documents/state-tennessee-v-scopes

3 American Experience, PBS. (2018, October 1). The Leopold and Loeb trial. American Experience | PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/monkeytrial-leopold-and-loeb-trial/

4 ACLU, State of Tennessee v. Scopes https://www.aclu.org/documents/state-tennessee-v-scopes

5 Darrow’s biography can be checked out and borrowed from the Internet Archive by anyone with a free account. https://archive.org/details/storyofmylife00darr/page/256/mode/1up

6 Soon to be in HathiTrust as a search-only volume. It can be checked out and read now by anyone with a free Internet Archive account. https://archive.org/details/centerofstormmem00scop/mode/2up

7 Mitchell, T., & Mitchell, T. (2025, April 24). Darwin in America. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2019/02/06/darwin-in-america-2/#:~:text=two%20camps

8 Adams, N. (2005, July 5). Timeline: Remembering the Scopes Monkey Trial. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2005/07/05/4723956/timeline-remembering-the-scopes-monkey-trial

9 Tennessee Virtual Archive, Tennessee Supreme Court Opinion of Scopes Trial: https://teva.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/scopes/id/157/

10 Branch, G., & Reid, A. (2024, February 20). 50 years ago: Repeal of Tennessee’s “Monkey Law.” Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/observations/50-years-ago-repeal-of-tennessees-monkey-law/

11 Adams, N. (2005, July 5). Timeline: Remembering the Scopes Monkey Trial. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2005/07/05/4723956/timeline-remembering-the-scopes-monkey-trial

12 Neuman, S. (2025, July 21). 100 years after evolution went on trial, the Scopes case still reverberates. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/07/08/nx-s1-5430760/evolution-scopes-creationism-monkey-trial

13 Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (1968). (n.d.). Justia Law. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/393/97/

14The Ongoing Fight for Evolution Education | National Center for Science Education. (n.d.). https://ncse.ngo/ongoing-fight-evolution-education

15 New civic biology: presented in problems : Hunter, George W. (1926 ) Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/newcivicbiologyp00hunt/mode/1up